About this work

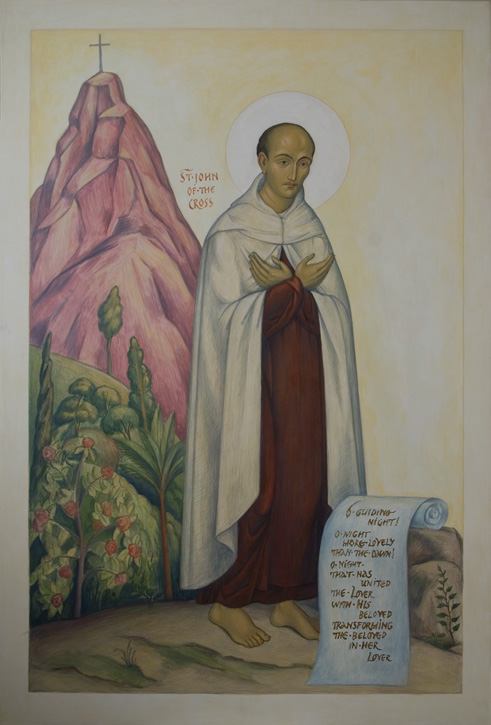

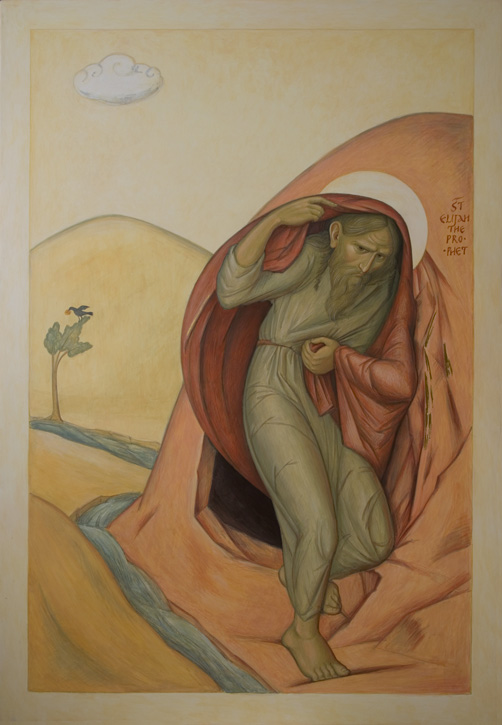

The far sides of the altarpiece show two great mystics and reformers of the Order of Carmelites, St John of the Cross and St Teresa of Avila. They flank the depictions of two pillars of Carmel: the Virgin Mary who typifies total availability to God and the prophet Elijah who typifies a burning zeal for God. In the centre is the Song of Songs, Bride and Bridegroom, Jesus Christ and the soul. Above them is a sombre reminder of the reality of evil and the price of love, the Crucifixion.

Another name for this work is ‘The Altar of Attachment’. My purpose was to convey the attachments which hold the whole of creation together: first of all, God's attachment to us; our response (and attachment) to Him; people's attachments to each other which does not differ from an attachment to God (God and humans are persons; the perfect expression of that fact is found in the Person of Christ, both human and divine).

I called it “Carmelite” because this is how I learned about the reality and intimacy of the relationship between God and the soul. It surprised me that Carmelite writings and practice can be easily translated into the language of human psychology, especially that of attachment theory, the concepts of true and fake self, and so on.

When St John of the Cross writes:

“Oh spring like crystal! If only, in our silvered-over faces,

you would suddenly form the eyes I have desired,

that I bear sketched deep within my heart.”

He speaks of the attachment of a soul to Christ. One can easily find this theme, of the intimacy between a human being and God, spun throughout the whole Bible. Anyone who has ever loved and been loved can grasp it. And so, using the terms of human psychology, the Carmelite way is simply the attachment of a human person to the Person of Christ and living the reality of that attachment here and now.

This vector of a healthy attachment to the person, human and divine, is the antithesis to the diabolical vector of abandonment which tends towards hell and tears creation apart. As it happens, abandonment is a typical state of a severely abused person, especially one abused as a child, even more so abused again within the Church. My conviction is that the remedy for the vector of abandonment is the vector of an attachment to Christ. The altarpiece is about this.

I dedicate this work to those abused as children and to those who were re-traumatized within the Church. My dream is to create ‘The Chapel of Attachment’ with this altarpiece where anyone who suffered an attachment trauma can come and pray. Until then, it is virtual.

The images and commentary below are organized in a deliberate way of walking from one to another. They are icons and require time to sink in. Please take time to ponder each of them.